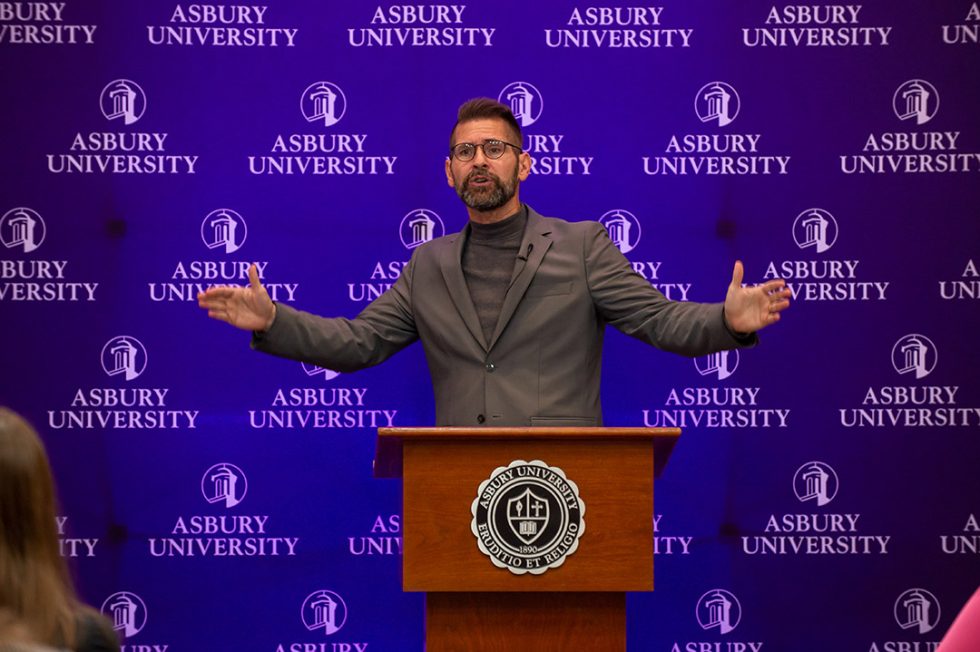

Reflections From Dr. Chris Bounds

Honors Program Speaker Discusses The Image of God, Incarnation, and Human Dignity

November 30, 2021

After Dr. Chris Bounds’s presentation to Asbury’s campus in October and fireside chat with the Asbury University Honors Program students (see: The Image of God, Incarnation, and Human Dignity), he provided some further thoughts via an interview. Here is the transcript of that exchange.

Q: What gives people value?

Q: What gives people value?

I like the word “give” in the question. The intrinsic value of people has its ultimate source in God. It is God, and God alone, that is the source of human worth and dignity. As such, this value is given to us by God. All other human value flows from this. While Church history has evidence to the contrary, in that we have not always lived up to our beliefs, it is this worth given to us by God, that has led the Church in its extensive philanthropic endeavors – social, political, educational, medical, and spiritual. David Bentley Hart’s Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies has been helpful to me in thinking along these lines.

More specifically, our value comes from being created in the image of God. The Scriptures make clear our greatness: humanity is created to be like God (Genesis 1:26-27). The Psalmist teaches that God has “crowned” us with “glory and honor.” (Psalm 8:5-6). Jesus affirms that as human beings we are “gods, sons of the Most High” (John 10:35) and Peter declares that we are “partakers of the divine nature” through Christ (II Peter 1:4). Humanity, as such, has dignity and value unlike any other part of creation. Humanity’s value in the end, however, does not come from what we do, although we work. It does not come from our human abilities, although we have capabilities unlike any other creature. It comes, in the end, from who and what we are – the image of God in creation, destined for full union with God. This is true for the entirety of our being as embodied souls. So we matter as persons, body and soul. We matter regardless of the worth society places on us. This is why the most vulnerable and most forsaken among us are the focus of particular attention by Christ and historic Christianity. God’s care and our care of them are the most tangible sign of this truth in the world.

Q: What are the implications of finding value in ourselves and others?

I will begin with the first – implications of finding value in ourselves. Jesus teaches us that we are to love ourselves (Mark 12:31). However, I believe it is important to realize that self-love is not self-generated. To be a person is to be a “being in communion” like God. I am only able to truly love myself, as I know myself to be loved by God and be loved by other people. A human “person” is not a solitary self, but is one formed in relationship, and only has completion in other persons. My love for myself, then, is only found in and through other relationships; most importantly God, but not apart from other human persons as well. Attempts at self-generated love apart from God and other people will always be malformed.

The most important implication of this is that I must find my end in God and others. Others (God and other humans) are necessary if I am to truly know my own self-value, to truly love myself. We, therefore, can’t live our lives in isolation, but must live in true authentic and wholistic communities. Another implication is that I love myself (take care of myself, nourish myself in body and soul) in order to give myself in self-giving love to others – to participate fully in reciprocating relationships of love and invite others into these “perichoretic” relationships mirrored in the Trinity. I love myself to be a blessing to others.

In regard to the second, I will not give as much focus, because this is more self-evident. The value of others is not found in what they can do or even in their gifts and graces, but it is in who and what they are as the imago Dei. This is signified historically in Christianity in two ways: (1) our treatment of the most vulnerable, neglected and devalued in human society and (2) our treatment of the human body in death.

Christ and his Body have exercised a “preferential option” for the poor and despised in the world. Focus is given to people who may have no recognizable value to society because they are inconvenient, have little or nothing to contribute to society, or brought irreparable harm. For one reason or another, they are deemed to have nothing to add to society. Yet, Christ and the Church serves and loves them. Why? Because they matter as creatures in the imago Dei.

Human value is seen in its totality in the way the human body is treated in death. Our human bodies image God and therefore are treated with dignity even when death has occurred. It is not just who we are that images God, but it is also in what we are as physical bodies. In death, however, our bodies have nothing to return to us, nothing tangible to offer to us. Yet, love, respect and honor are given to the body in death. Why? Because even our bodies image God.

One of the most important implications of this, and a recurring theme is my responses here, is that Christians and the Church must continue to focus on “the least and last” in the world. It is the most tangible sign in the world of human dignity and glory given to humanity by God.

Q: Why is it important for us to consider questions such as these?

These questions must be kept continually before us, lest we forget. Because of the fall of humanity through our first parents, we are prone to loss of memory. Without remembering, our default setting is human abasement.

There is a wonderful Greek word that should be at the forefront of any Christian understanding of humanity. It is the word “anthropenē,” which means “the art of being human.” Every human generation is threatened by the loss of anthropenē. We must continually ask these questions in our cultural contexts, lest we lose sight of the “art of being human,” being creatures in the image of God.